Something’s happening with maths confidence… and it’s not all good.

I’ve been digging into the TIMSS data again for a video I’m working on. Last week, I shared a post about the widening gap between the highest and lowest achievers in England. This week, it’s confidence I want to highlight.

TIMSS doesn’t just ask pupils maths questions – it also asks how confident they feel in their own mathematical ability. While our overall achievement has been heading in the right direction, there are some quieter underlying trends we can’t ignore.

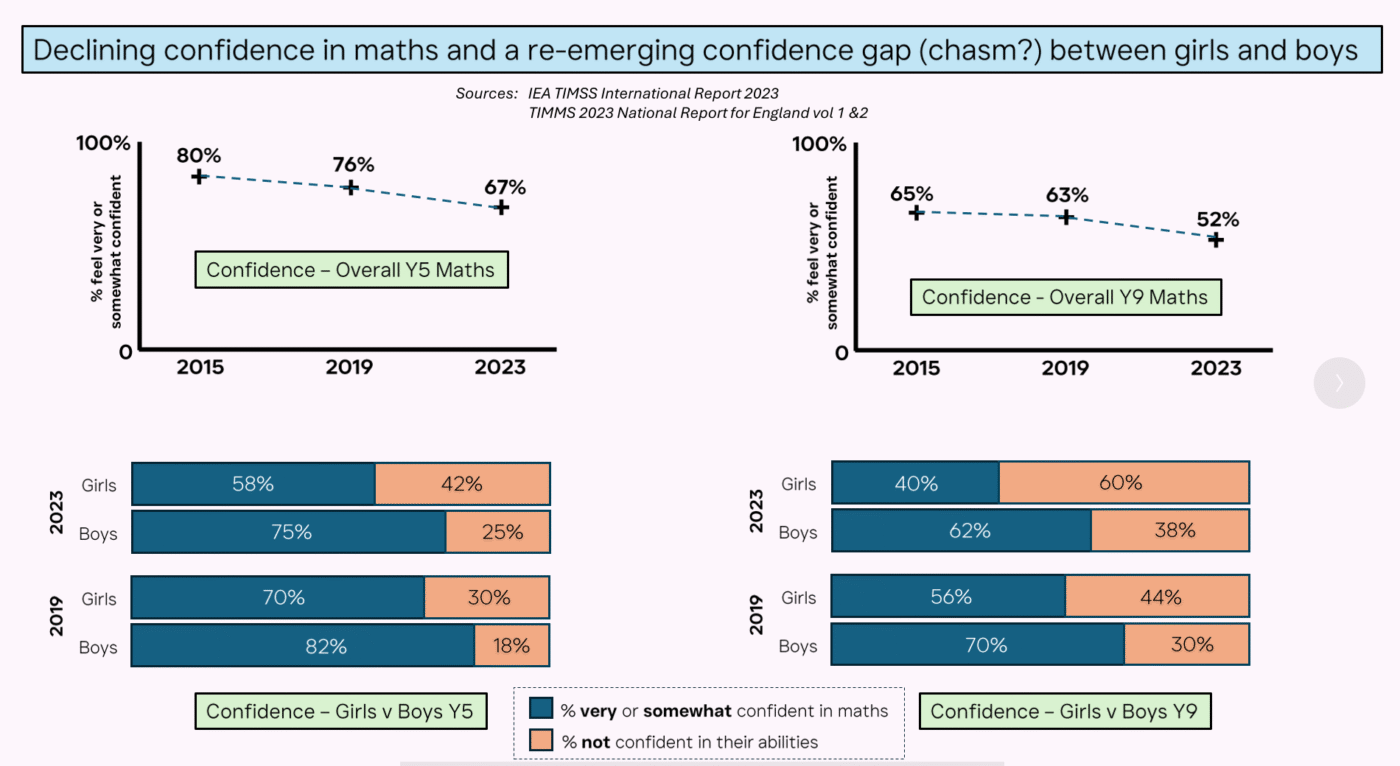

Trend 2: Confidence has been falling since 2015.

In 2023, just over half of Y9 pupils in England said they weren’t confident in maths. In Year 5, things look a bit better, about two-thirds say they feel confident, but that’s down from 80% in 2015.

One statistic stood out from the Y9 data. 6 in 10 girls say they’re not confident in maths. If you take that seriously, it means in most Y9 classrooms across the country, the majority of girls are now feeling unsure about their ability. England now has the largest gender gap in maths confidence of any country that took part in TIMSS.

To be clear, this isn’t about criticising what’s gone before. There are brilliant people doing incredible work every day, and the report shows lots of positives too: maths enjoyment is still high, and we’ve got more very confident pupils than many other countries even those that perform more highly. However, confidence seems to be clustering. Those who feel confident are pulling further ahead, and those without it are falling further behind. The divide is growing.

Of course maths confidence doesn’t exist in a vacuum. While I was writing this on Sunday, I read headlines about rising anxiety among teenage girls, with many missing school because of it. Clearly something broader is going on.

Some immediate questions

1️⃣ If our Year 9 pupils have lived through the biggest wave of maths reform in recent history, why isn’t that showing up in their confidence? They should, arguably, have benefitted the most. Some clearly have, but those benefits haven’t been evenly felt.

2️⃣ Did the 2014 curriculum and assessment reforms disproportionately impact girls? Has a packed curriculum played a part?

3️⃣ Has COVID widened gaps that were already there?

4️⃣ Most importantly, why are so many girls feeling this so strongly?

Does this reflect what others are seeing in your own classroom, or in the schools you work with?

At Rethink Maths we’ve made confidence one of our core missions. Reports like TIMSS are a reminder of why it matters. When children feel confident in maths, they learn more, achieve more and they’re more likely to enjoy it too.

So how do we build that confidence, for everyone?

P.s. I know this data has been out for a while now, but I thought it important to revisit. As we start thinking as a country about what comes next, we’ll need to not only sustain the progress we’ve made but find ways to close this growing divide.